Speculating on a Global Approach to Achieve Jazz Phrasing

© Mark Eisenman 2015

note: there are hyperlinks to musical examples in this document.

In trying to achieve the goal of sounding like a jazz musician, the challenge is to figure out how to approach the task. The most important element of jazz in my opinion is the rhythmic aspect. One only needs to hear a four-measure fragment of Philly Joe Jones playing un-accompanied to know that it’s jazz music.

With this in mind, I will attempt to come up with a theory of the “how to” of jazz rhythm.

Although my aim is to have the theory be useful, (i.e. operative) it involves a great deal of speculation.

I will try to understand and describe the rhythmic approach of a small number of jazz players. From this understanding, I will try to glean some speculative principles that might be useful to any aspiring jazz musician. The reason I seek a speculative approach is that I believe that by doing this the player will have a deeper approach to the task of jazz improvisation. My hope is that this approach will not sound as derivative as some other methods, allowing the player the freedom to express his or her own voice, while still doing the things that sound ‘jazzlike’.

While it is absolutely essential to immerse oneself in the sound of great players by lifting, analyzing, and playing their solos, that is just the beginning in learning how to PLAY like them.

With this goal in mind, it becomes clear that if I can understand how jazz musicians think about what they do, I could use their approach without merely parroting or mimicking them. This would be a much subtler method and much more open to “in the moment” inspiration. It also would be much less obvious to the listener than merely copying the content of a given player or set of players. The essence of this approach is to understand the process of playing jazz, not only the resultant music.

Perhaps the best thing about this way of thinking is that even if my approach is wrong, and a player that I have studied would never know, or admit that my theory of his approach is valid, I will have made it a principle of mine, and if it works for me, it may be transferable to others!

The idea of trying to get inside a player’s head came to me years ago.

I had transcribed one chorus of a solo by Zoot Sims on “I Got Rhythm”. The notes that I transcribed and how they related to the chord was not nearly enough to account for the great affect the solo had on me. After looking at the notes on the page, I was disappointed because nothing surprised me! Everything was explainable, except why it sounded so good. I decided that I was looking in the wrong place. It was obvious that the rhythm was the reason for the effect. After looking at the shapes of the line and the fine detail, I realized that the rhythm that was so captivating was happening in larger units. This rhythm was happening at the level of phrase. I was finally hearing the sentence structure of the music, not merely the words. I tried to understand what Zoot was doing by putting the transcription away and starting with a blank slate. I wanted to see the larger structure, to understand where and when he began and ended his lines in relation to the form. I drew 8 measures of music on a piece of paper, 4 measures to each line and followed the empty measures with a pencil and made a mark when Zoot started a new line. The tempo was medium up (M.M = 256). Within one chorus, a general pattern emerged. For example, the lines tended to begin in even numbered bars. The line would continue through part of or the entire next bar. This had the effect of always feeling as if the music was going somewhere. These bars typically have the iiv7 –V7 harmonic progression ( IE: the dominant, or moving harmonic function) of the tune.

By starting lines in even numbered bars, Zoot was always playing through the chords that were moving to resting points. This approach was even evident in the melody chorus, before the solo began!

The best example of this is that in the bridge, where the harmony of the tune takes a large leap in key area (from Bb in bar 16 to D7 in bar 17) Zoot most often started his line in bar 16 and successfully negotiated the change in tonality in midstream. The natural tendency for unsophisticated players is to play on the D7 chord by waiting for it. This creates a lack of flow in the phrase. Zoot seems to consistently leave a space in bar 15 and begin his line in bar 16 and then lands somewhere in bar 17 or even later. Zoot Sims’ playing shows one of the most important aspects of jazz phrasing. There is a difference between playing ON the changes and playing THROUGH the changes. Zoot Sims plays through the changes, all good jazz players do.

It should come as no surprise that Sims would have this phrasing concept down, seeing as he was one of the great tenor players that came strongly out of the Lester Young school of jazz playing.

So it’s important to take a moment to check out Lester Young’s solo on “Lady, Be Good”:

Just have a look at the solo as the transcription flows. Unfortunately the transcription break a cardinal rule of displaying FORM.

It would be easier to see what I am talking about if there were 4 bars per line and every line started with an ODD numbered bar… (1, 5, 9, etc) and ended with an even numbered bar (4, 8, 12, etc.)

I urge the reader to do that work themselves to really visualize what’s going on phrasing-wise.

Note where the activity happens rhythmically. This ONE solo provides an archetype for this whole concept, and for thousands of jazz musicians that came after him.

A great example of this is here, bar 32 of the form. NOTE how Young starts the upcoming chorus on bar 32, NOT bar 1. The link takes you to the last 8 of a chorus to give your ear a chance to find the form.

_____________________________________________________________________________

I called this concept Even Goes To Odd.

I decided to try using this as a tool to change my phrasing, and with any luck, improving it. I found that it yielded some interesting results.

The first thing I noticed was how difficult it was. This confirmed one of my other theories about learning to play. As a young player, I noticed that everything that felt natural when I played usually sounded stiff and un-natural. Therefore, I decided to try awkward things out of desperation. Strangely enough, this often sounded better. The fact that my attempt of Zoot’s phrasing felt awkward emboldened me to think I was on the right track.

The second effect was that it forced me to negotiate the chord changes in ways that up until then I had been missing. For example, it was completely new to me to try to start a line in measure 16 (Bbmaj) and land gracefully (I hoped) somewhere in measure 17 (D7) or even 18.

The third effect was even subtler. As a teacher, and a player, I often have to deal with the problem of a student (or me) playing too much. When a player plays too much, without leaving any space he often stops listening. This can lead to serious rhythmic problems, and generally is antithetical to making good jazz music. I realized that in order to deal with the challenge of phrasing like Zoot, I had to leave some space. I could not very well start a line in a given measure if I didn’t ever stop! This solved a great problem for me as a teacher as well. If I have a student who is playing too much, (this is especially a problem in pianists, because they don’t ever have to breath.) I never tell him to play less, or say, “You’re playing too much”. I simply ask him to try to start lines in certain places. In other words, I am asking him to accomplish a positive task, not eliminate a negative habit. This is a much more positive approach than saying, “Don’t do that”. I have refined some of these ideas further and will deal with that subject later.

Upon close listening, it is obvious there is much more to jazz phrasing than can be explained by Even Goes to Odd. It concerned me that in reality, nobody played like that all the time, and this made the theory less than convincing. How could the theory account for Zoot or anyone else starting a line in measure 1 for example? The following explanation might seem contrived, but I will attempt to account for this problem.

In the same way that a boulder and a pebble are perfect examples of rocks, and that a tree’s branches use the same basic rules of branching as broccoli or our circulatory system, scaling of rhythm is inherently useful. The concepts that work for rhythm are applicable across large and small units of time, in the same way that a boulder and a pebble are both ‘rocky’, and indistinguishable from each other without some external constant or something with which to compare them.

Therefore, the key to expanding the use of the theory and therefore defending its viability is to realize that the concept of Even Goes to Odd can work at multiple levels of time or scale. It is not restricted to the level of measures (i.e.: phrasing).

If one were to apply the theory to the level of half-measure units the effect would be to play across any barline. It would cause the player to deal with starting his lines in the second halves of any measure, including odd numbered measures. In “I Got Rhythm”, this would create the effect of dealing with the chord in second half of measure 1 G7 and getting to C minor in measure 2. It is obvious that we could continue to scale down the application of the theory to smaller units of time. The next level would be the quarter note level. Therefore, beat 4 leads to beat 1. To experience the effect of this, turn a metronome to 100BPM and at any time count 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 etc. in time with the metronome, without any accenting. This represents the way most people hear time. Next, contrast that feeling with the application of the theory. Turn the metronome to 100BPM and at any time count 4 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 etc. in time with the metronome. The effect should be that beat one feels like a consequence of beat four. Jazz musicians that swing at the quarter note level feel time this way. They don’t even think they are syncopating, they are just playing the time as it really goes! To go further down in scale, eighth notes swing harder when conceived as starting on even numbered eighth note. Doo-Ba Doo-Ba Doo is not the way players who swing play. A much better way to feel the eighth note line is BAoooBAoooBop where the “Ba” represents an upbeat (even numbered eighth note) and “ooo” represents the following downbeat. Please note this technique has the added benefit of getting a legato phrasing WITH accenting. It connects the up-beat eighth to the following downbeat in a much more natural and accessible way. It sounds like air is going through the whole line when a player gets the hang of it.

Barry Harris’ use of the Be-Bop scale is a way to achieve the same effect by placing all the non-chord tones (or upper extensions) on even numbered eighth notes. Because of the tension these notes have against the underlying harmony the notes stand out, and to the listener, cannot help but sound accented. This helps the eighth note line have the Even to Odd feeling.

The explanation of scaling can work in larger units as well. For example, at faster tempos one merely has to scale the theory up to full measures (which we already covered with Zoot) or even 2 bar units, Charlie Parker playing Cherokee for example. This is no surprise as Cherokee is actually a 64 measure tune, so if Parker was feeling it in half-time (32 measures), (advisable at a blistering tempo), he ends up playing phrases that are in even numbered bars at that scale.

The amazing thing about the best players is that they seem to use, consciously or not, this concept at all levels of time, at any time.

The shapes of lines can also be understood using this concept.

A good line may have a series of eighth notes, seemingly rooted in phrasing that is ODD to EVEN but the high points and changes of direction in the line have the effect of forward motion because they happen on even numbered eighths, quarters or half-measure units. (See Bud Powell, “Cherokee” bar 3, beat 2, and beat 4, change of direction on bar 5 beat 2.)

One can see other evidence of this if one tracks the tendency of a given player to play embellishments (triplets, mordents, etc.) on certain places in time.

(Powell, “Cherokee” bar 0, pickups on beat 2 with a triplet)

Bill Evans’ solo on “What Is This Thing Called Love” from “Portrait in Jazz” is consistent in the first 10 measures in starting every line on an upbeat. (Even to Odd, on the level of eighth notes). (As a side note compare the start of this solo to the start of Wynton Kelly’s solo on Freddie Freeloader, where the 1st downbeat on one occurs in BAR 8… ENDING a line)

His ideas continue through the form in the same manner as Zoot Sims, but to a greater degree. See the last 2 bars of the bridge where he plays 2 upbeats, starts a chromatic line that completely obscures the beginning of the last A section but successfully negotiates the chord change Gmin7b5 to C7 with a perfectly timed 7th falling to 3rd as the chord changes between the first and second bar of the last A section! This last, represents Even to Odd at the level of large-scale phrasing. The large scale use of this technique is taken further up the scale of phrasing in the second chorus, where the first eight measures have lines that begin in bar 2 and go through bar 3 and part of 4, then a complete rest in bar 5 to set up the next line in bar 6. This use of large-scale rhythmic logic gives a sense of structure that carries the listener through a longer path. It seems that the detail in the line merely serves the purpose of having something to play in those places. Bill Evans’ genius was that the content is very logical at the smaller levels of phrasing and eighth notes, and correct in the harmonic and melodic sense at the same time!

A fine example of the Even to Odd theory is found in Bud Powell’s solo on “Fine and Dandy” measure (16-18). In fact Bud is so hell bent on this phrasing idea, that he starts is his solo before Sonny Stitt is even FINISHED his! He leaps in on bar 32 of Stitt’s last chorus, overlapping him. Who knows if Stitt was even intending to stop?

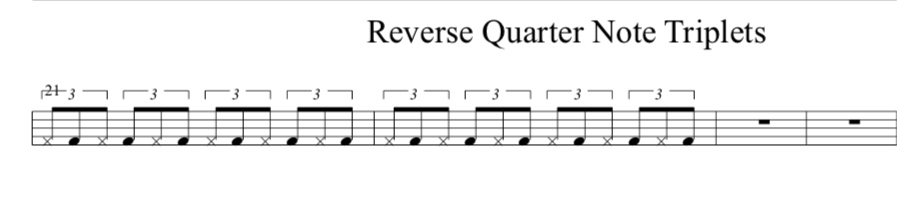

This theory also explains one of the least addressed and most used rhythmic features of jazz music. At slow to medium tempos, the use of the quarter note triplet in jazz often is employed starting on beat 2 or 4 or the up-beat before 1 and 3 or the middle part of the triplet after beats 1 and 3. Compared to the way most quarter note triplet figures are taught, jazz musicians play them backwards. Yet, the effect of starting quarter note triplets on beat 2 or 4 is huge.

Mastering this in you jazz language is absolutely a MUST to play slow to medium slow tempos.

It changes phrasing in the same way that Even To Odd does. The use of this figure occurs in rhythm sections, especially comping. Listen to “Coltrane Plays the Blues”, McCoy Tyner on “Blues To Elvin” at 40 seconds, 45 seconds in fact all the way through the recording and you’ll hear this. Another great example of BOTH types of quarter note triplets can be found here, the reversed (2-4-2) versions (the note-heads in the notation below) at 5:09 Bobby Timmons, and here at 5:44for TWO whole bars, and examples of the regular 1 to 3 to 1 (the Xs in the notation below) quarter note triplets here and here in the melody chorus.

I have more examples of this theory in transcriptions that I have done. It seems as a player that this way of understanding jazz time is very useful. It certainly helps me. While the players that appear to do this probably do not even think about it in the way I have described; it is a useful theoretical explanation how players play rhythm at all time scales. It is descriptive, but also meant to be implemented in the act of playing and practicing jazz rhythm.